Brexit graduate

Brexit graduate

Brexit graduate Voters without degrees were more likely to back leaving the European Union, figures suggest. But in one of the towns with the fewest graduates in the UK, the relationship is more complicated than it first appears.

Sam Bozic knew university wasn’t for him. He was bright and ambitious, but simply memorising facts and regurgitating them in tests? That wasn’t learning, Sam thought.

So he left school as soon as he could and trained on the job as an engineer. Now Sam, 21, is setting up a web design company with two friends. Unlike all the recent graduates he knows, he isn’t saddled with student loans.

“You have to pay off so much debt,” says Sam. Outside a coffee shop in Corby, Northamptonshire, the afternoon sun shimmers against his MacBook Air. Closely-typed work documents are strewn across the table. “It’s just too much money.”

In Thursday’s referendum, Sam didn’t vote.

He was too busy to study all the pros and cons, he says. His parents – Serbian refugees who fled the war-torn Balkans when Sam was four – urged him to cast his ballot and make his voice heard.

“But with working so much I didn’t have time to fully read up on it,” he says. His business will be fine whatever happens, he thinks. “I’ll just keep doing what I’m doing.”

- Follow the latest developments on our live page

- Corbyn unveils new team after walk-outs

- Johnson pledges EU co-operation

Sam lives in a town where just 14.9% of the population have university degrees, according to the 2011 census. Only two other areas – Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, and Castle Point, Essex – have fewer.

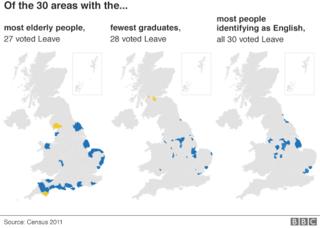

Along with age, class and the part of the UK you live in, graduate status was one of the key factors that influenced whether or not you supported EU membership, election analysts believe. Of the 30 areas with the fewest graduates in the UK, according to the 2011 census, 28 backed Brexit.

Corby was one of them, with 64% voting Leave.

By contrast, 29 out of the 30 areas with the most graduates voted Remain, including the City of London (where 68.4% are graduates), Belfast South (50.1% graduates), Cambridge (47.3%), Oxford (42.6%) and Edinburgh (41.4%).

Young Europeans living in Cambridge offer their views on the UK’s Brexit vote.

The polling industry might be treated with scepticism since the 2015 general election. But a survey by Lord Ashcroft of 12,369 referendum voters after they had cast their ballot was emphatic. It suggested 57% of those with a university degree voted to remain, while a majority of those whose education ended at secondary school or earlier voted to leave.

Corby suggests the link isn’t entirely straightforward, however. Sam may not have a degree, but as a trained engineer he’s hardly uneducated. His age may have been a bigger factor in his abstention. Turnout was lowest in areas with more young people.

Crucially, he lives in a town where for decades people were used to securing skilled, well-paid jobs in the local steel industry without having to earn a university degree first.

An apprenticeship at the Stewarts & Lloyds and, later, British Steel plant was a passport to a comfortable lifestyle. The town was nicknamed “Little Scotland” because so many Scottish workers poured in to work. Corby still holds a Highland Gathering every summer.

But the closure of the steelworks in the early 1980s led to soaring unemployment. Regeneration has helped the town recover and Corby still has a strong manufacturing sector. But the fading 1960s shopping precinct doesn’t offer the town’s young people the opportunities it once did.

At Jan’s Sweet Shop in Corby’s indoor market, students often come by outside term time looking for work. “We had one in yesterday,” says owner Janice Taylor, 69, as she pours pear drops from a jar into a paper bag. She doesn’t have any jobs to offer. “I feel sorry for them.”

Janice runs the stall with the help of her husband, Barry, 76. Many of the sweets they sell have a Caledonian theme – whisky fudge, Scottish toffee, sugar Peebles, fizzy iron brew.

Both Janice and Barry voted Leave. For Janice, the big issue was immigration. There are simply too many people coming in to the country, she says. And if Scotland leaves the UK as a result – well, that’s up to them. Barry remembers the days before the Common Market, and he thinks they were better.

Divided UK

In light of the EU referendum result, which split the country almost down the middle, this week BBC News Online will be looking at ways in which Britain is split. On Tuesday, we will be looking at the generation gap, from Sunderland.

He grew up in an age when you didn’t need to put yourself through a degree to better yourself. He left school at 15 for an apprenticeship as a pattern grader at the nearby Dolcis shoe factory on 2 a week – decent money for a teenager in the mid-1950s.

Then he joined the Royal Air Force, where he trained as a nurse, and from there went into the steelworks. “It wasn’t my cup of tea but it was good money,” he says. “You could if you wished go from one job to the next in those days. It was quite easy.”

With all these skills at his disposal, Barry resents the notion that a lack of a degree somehow diminishes his right to hold an opinion. He’s learned more about the world from a lifetime of work than he could in any classroom.

Janice says she agrees with Justice Secretary Michael Gove that the British people have “had enough of experts“. She didn’t trust those who said Brexit would damage the economy. “I think they are in a more comfortable place than I am,” she says. “They’ve already got jobs, they’re safe. For ordinary people, it’s different.”

Plus, she says, “they don’t always get it right”. Didn’t lots of experts argue that the UK should join the euro? Didn’t they tell her not to worry about rising immigration?

Much was made of this during the referendum. The Guardian’s Polly Toynbee said the Remain campaign saw “eager young London graduates” making little headway with Brexit supporters.

But there were also worries that discussion of this degree divide was often shaped by snobbery. After the results came in, Leave activist Mark Wallace wrote that his Facebook feed “was filled with an outpouring of bile against those less well-educated” from angry Remain voters.

Outside the indoor market, Mark Hale, 47, sits on the wall and rolls a cigarette. He trained as a stonemason and then as a printer, but the last few years have been hard for Mark. “I’m unemployed. It’s not good. I’m on the sick. It’s a whole culmination. Redundancy. And I drink.”

Mark voted Remain. Until he was eight and his family moved south, Mark lived in Stranraer, Dumfries and Galloway. He wanted Scotland to stay in the UK in 2014 and he thinks the slogan of that year’s No campaign still applies: “I think we’re better together.”

The importance of the education gap is overplayed, he believes. “It doesn’t matter if you’re college educated. I mean, look at Boris Johnson,” he says.

“They’re trying to create this idea that working-class people are all knee-jerk. Well, I don’t believe that’s the case. It’s the mismanagement of all governments that caused this result.”

Mark’s friend Andrej Berezin, 38, is listening carefully. He didn’t go to university either. A Russian-speaking Ukrainian, he moved to Lithuania as a teenager, which meant that after a long stint as a ship’s chef he was able to move to the UK on an EU passport. When he arrived he took a job in a nearby Argos warehouse. These days he works as a photographer.

He disagrees with Mark. He thinks education did play a part in the referendum’s result.

Andrej handed out leaflets for the Remain campaign. At first, every British-born voter he spoke to told him they were voting Remain. But then all of a sudden, “on Facebook they were saying ‘We’re using pens to vote‘”.

“I’ve not come here to use the benefit system or to kill and rob people,” he says. “I’m constantly doing things for the community.” He reels off a list of charities for whom he volunteers – a local art gallery, the friends of Corby’s Coronation Park, a homeless shelter The Woodland Project.

It’s not malice that drives suspicion of foreigners and conspiracy theories, he believes. “Some of the people here are not educated good. They don’t have access to the information in full.”

Political scientists will argue over the significance of education status in the referendum. You don’t need a degree, however, to see how Corby’s recent history played its part in the result, too.

All photographs by Phil Coomes

Read more: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-36624413